There are many motivations behind what we do at Plenty Canada. Some of these are driven by the urgent need to preserve biodiversity. Our plant and animal relatives have as much right to live and thrive as we do. The current rates of biodiversity loss exceed the historical past by several orders of magnitude. This must not continue. We are also driven by matters of equity and justice, particularly those involving Indigenous peoples. Health, education, language retention, these are all subjects that are critically important to us as evidenced by the projects we undertake. And we try our level best to embrace and advance our motivations within a social and institutional culture that nurtures and supports the growth and development of youth, of our precious resource, our current and future generations. I’ll soon be seventy-four years old. At this age I’d like to think I’ve learned a few things. None of us are as perfect as we’d like to be, and I’m certainly no exception. But one of the attributes I and others have tried hard to imbed within our organization is the concept of respect, based upon longstanding ethical standards and intergenerational principles of affirmation, cooperation, and partnership. During our regular organizational meetings, when I look at our staff, contractors, advisors, and volunteers, I mostly see people who are young enough to be my children or grandchildren. I make this observation not to diminish their standing or stature in any way, but to the contrary, to marvel at their capacity, their intelligence and energy, their embrace of decency, their support of each other, and their clear thinking about the challenges that lie ahead. As a modest not-for-profit charitable organization in its 46th year, Plenty Canada has experienced both highs and lows and witnessed hundreds of remarkable people, from all over the world, come through its doors. I’m struck by the commonalities shared among members of the human race. Within the “zone of consciousness” that our organization operates, I’ve come to realize how much community-based peoples seek the same things in their lives, not just for themselves, but for the environment that supports them and for making decisions that achieve sustainable development goals for their children and future generations. So, it often seems discordant that while our circle possesses a firm intellectual and evidence-based comprehension of causes and solutions to certain problems, and a value system that contains empathy, many others in the world do not. Power seeking, self-aggrandizement, greed, these are not the values we embrace or in any way honour. For us moving forward and for the world to move beyond its current spate of existential threats, we need to evolve a global culture that places an emphasis on taking care of each other and the environment. We are but one humble organization that partners with other like-minded organizations to conduct works we believe correspond to these values. In this regard, I encourage you to read the articles in this newsletter and to peruse our archives found on Plenty Canada website’s News and Blog page. And I thank you for your interest and support of our work. Chi Miigwech. Niá:wen. Merci. Thank you. Larry McDermott Executive Director Plenty Canada

0 Comments

Throughout these past few years, Plenty Canada has aimed to place an increasing emphasis on the promotion of Indigenous culture through education, including language revitalization. Despite colonialism, Indigenous culture of an incredibly large variety has sustained itself for centuries within Canada, and Plenty Canada would like to play a part in reminding the public of its value.

To that end, Plenty Canada is hosting a series of Anishinaabemowin (Algonquin) language courses led by a long-time partner of ours, Barry Sarazin, and his wife Jessie-Ann Sarazin. These courses are being held on Zoom from January 6th to April 5th, every Tuesday and Thursday. Each lesson begins with singing and drum songs conducted by Barry and Jessie-Ann, followed by a prayer (usually given by Jessie). After this, the technical part of the lesson begins. Barry presents a video reminding participants of the different vowel sounds used in the language, followed by a lesson plan which includes Algonquin words along with their meaning and pronunciation, as well as common sayings relating to whatever that day's topic happens to be. True to Barry and Jessie-Ann's overall focus, there is also a ton of storytelling included in each session, from personal experiences Barry and Jessie-Ann have had to traditional Indigenous Algonquin stories. Despite the difficulty of holding such a technical interactive course online, the program has been a tremendous success, welcoming people of all ages and backgrounds. The success is, of course, entirely due to the cultural expertise of Barry and Jessie-Ann, knowledge and skills they have honed through years of work and training. Barry is an Algonquin elder and fluent Algonquin speaker from the Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, who has been involved in fostering cultural development for decades. All the way back in 1981, he was involved in community and economic development with the Anishinaabek First Nation. He followed this up by spending a good deal of the 90s learning songs, oral histories, and sacred teachings from traditional teachers, as well as involving himself with various other community initiatives, such as youth teaching workshops. What's more, Jessie-Ann is also an accredited Algonquin language teacher, with a certificate from Lakehead University. She, like Barry, is quite adept at a number of different traditional art forms, such as bead and moccasin making, hide tanning, and regalia making. While Barry and Jessie-Ann dedicate a large amount of time to language training, they are also broadly interested in communicating Indigenous arts to the next generation, keeping these proud and incredibly varied traditions alive. Fortunately for them, the program has been quite well attended so far, with over 150 people registering to participate. This is a very encouraging number, especially considering that Plenty Canada hopes to hold similar online and in-person seminars in the future. Given the success of both this program and the mini birchbark canoe making workshop last year, it seems that cultural education programs will remain a very important pillar of the organization's overall mission. — Breton Campbell We are happy to announce that we have received support to continue working on the Ginawaydaganuc project. Ginawaydaganuc is a word from the Algonquin language that loosely translates as “the interconnection of all things.” It is an Algonquin principle outlining our responsibilities to each other and the earth. Our Ginawaydaganuc project is collecting stories about good work being done in Indigenous communities to support Indigenous food sovereignty, especially in the face of challenges made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. We are getting ready to begin a second round of interviews to learn from more Indigenous people about what food sovereignty means in their communities. If you or someone you know is passionate about food in your community, we would love to include your or their perspective in this project. Please reach out to Sarah Craig at [email protected], or Rosie Kerr at [email protected] for more information.

Food sovereignty is the right of a people to have access to healthy culturally appropriate foods, to grow and harvest foods produced through sustainable and ecologically sound methods, and for communities to define their own food systems. In our interviews so far, we have heard about the cultural importance of community food and medicine sharing for many communities, especially during COVID-19. We have also heard about the importance of mentorship, youth involvement, and Indigenous languages in the revitalization of Indigenous food practices. We have learned from those we have spoken to so far that food sovereignty doesn’t always begin with food. True to the name of our project we have heard about the connections between food and many other aspects of communities, including water, land, medicine, mental wellness, housing, and community infrastructure. There are of course many challenges in this work and we want to hear about those too. Part of this project is working to make sure Indigenous people are heard when it comes to policies that affect their lives. We plan to create articles highlighting diverse perspectives from across Turtle Island (North America). We also plan to create a knowledge sharing platform where Indigenous peoples can learn, connect, and share resources to build food sovereignty programs that are informed by traditional cultural practices as well as modern farming methods. Ginawaydaganuc hopes to help foster connections and relationships toward building community-driven food systems change. — Rosie Kerr Plenty Canada’s Maya-Guatemala project involves the preservation of cultural values and traditional knowledge. Elder women, traditional weavers, are teaming up with young women to revalue and safeguard the ancestral knowledge of the Maya Q’eqchi’ people, “uniting in defense of our beliefs and values that roots us in our Mother Earth, the Mountains and the Cosmos,” as stated by Maria Leonor Teni de Leon (Maya-Q’eqchi’), project coordinator.

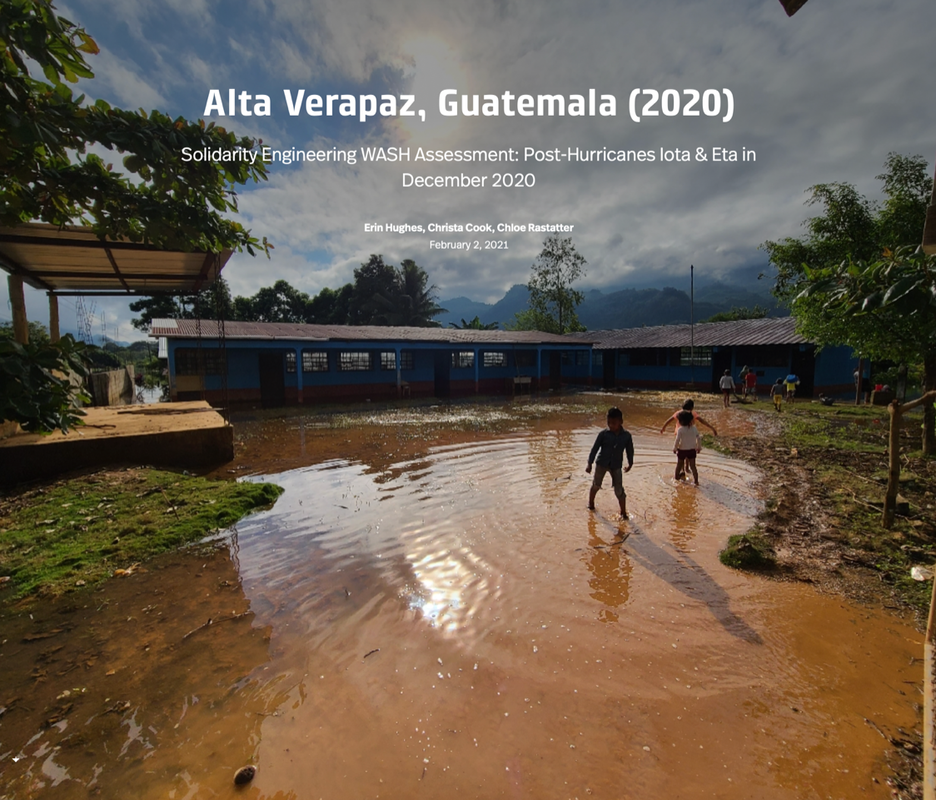

In difficult times of pandemic and economic instability, the Maya-Guatemala project has provided much needed information and distributed masks as well as facilitated vaccinations to elder weavers and their families. “Our strength as women and our commitment to our Maya culture are the basis of how we work,” said Teni. Fifteen Q’eqchi’ women weavers formed the first circle of the project. As elders of extented families, and community leaders, they came together in 2020. The primary intent of the project is the preservation of the ancient weaving arts, but with the COVID-19 pandemic in strong upswing in the first two years, the group began by responding to that challenge. Many families were suffering serious hunger; the weavers reasoned that they would focus on the most pressing needs of the community. They reasoned that their project is “guided by love” and they worked to secure much-needed assistance in foodstuffs and medicines that were channeled to over 200 families in three communities. “Our foundation is the value and knowledge of the Maya Q’eqchi’ feminine force,” said Teni de Leon. “We take stock of our elders and can see that many are very marginalized, the older women, many widowed, are our treasures and they are often living in severe poverty with very poor housing.” The impacts of climate change are palpable. In November 2020, two back-to-back hurricanes were unusually penetrating. They caused widespread flooding that damaged the foundations of many houses. Among the elder’s families, many houses are in dire need of repair. “As we see the many ways we need to support our elders, we are determined to help,” expressed Teni de Leon. A team with house construction skills was organized but there is a need for further resourse development in this task of home repairs. As the elder weavers retie the family networks within that central tradition, an Indigenous way of resilience restrengthens that is guided by reciprocity. Catalina Xo, a community Elder leader expresed that the weaving tradition in itself is a way of life, inclusive of all nature and the spirit and the vision to protect, care for, and develop their community and their lands. Teni de Leon reports that the weaving sessions are now in full swing. The younger women take care of their elders and assist them in their daily work in the corn and bean fields, in the gathering and preparation of medicinal plants. Among the elder weavers are midwives and healers of various types, with many traditional culinary skills. Instruction sessions are in full swing and the group has visited with other Indigenous weaving circles in the region. Within this ancestral knowledge are carried the cosmovision and cultural teachings that guide a community. These teachings are essential in the raising of young children. “The more ancient weaving patterns carry stories and symbols important to our people,” said Teni de Leon. “The elders are particularly enthusiastic that the teaching is in the natural style of the Q’eqchi’ people and culture, where everything is related.” SEE HURRICANE STORY: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/9ac4f7acee2941aebcf9fc15a80e4185) — Jose Barreiro Plenty Canada’s Caribbean project, Cuba Indigeneity: Values and Knowledge, is based in the remote mountain and coastal region of eastern Cuba, the Oriente. It partners with a significant population of Taino-guajiro (rural) Indigenous kinship families under the leadership of a traditional cacique (chief), women elders, and a new generation of leaders.

A recent visit to the community of La Rancheria found the folks active and in good spirits, despite coping with a difficult economic and public health moment on the island. Cacique Panchito and Grandmother Reina received us warmly, and we had a chance to hear from a good variety of voices on the situation and conditions of life in Cuba this season. It takes a rugged jeep and transfer to a soviet-era tank-like truck to traverse the steep and deeply rutted mountain roads to reach the valley enclave that is La Rancheria. This is the village (yucayeque) of the cacique, recognized as an “autochthonous community,” and considered a model agricultural community. In the past year, Plenty Canada’s project with the Gran Familia has focused on community-building activities. The harsh United States policies of economic blockade, plus the pandemic of the past two years have made life exceedingly difficult, causing many shortages in food, medicines, transportation, and other items. The communities’ leadership circles have now coalesced as a working group among six communities (Cajobabo, Veguitas, Yateras, La Rancheria, Fray Benito, Tames). Forming into a mutual-help collective, the working group has led and assisted projects among several core Taino communities. This was precisely the early instruction and aspiration of the Native community elders in Cuba. Urged by Cacique Panchito, they spoke of the need to tie back together the dispersed large families of the Taino kinship group, the Rojas and Ramirez families. Over forty years, from the 1980s, this main clan of Native people in Cuba, has been gathering its elders into discussions about “weaving” the communities. They prioritized the passing of, “Values and Knowledge,” (Valores y Saberes) among the generations. Large annual gatherings and many local workshops over the years achieved a remarkable revitalization of consciousness of indigeneity. It also spawned a growing circle of mature family and community leaders who have enthusiastically organized volunteer working groups, “brigades,” that have focused on generating sustainable development projects. At La Rancheria, a water project is underway that taps into more voluminous sources, and the group is building tanks and piping to the twelve houses in the community. Some weeks ago, they assisted the community in fully rebuilding their “caney,” or circular, thatched-roof structure where meetings and ceremonies are held. Beans and coffee are occasionally dried on the concrete floor of the caney. In the cities, availability of basic foods is scarce and always worrisome. No one starves but people struggle seriously to find affordable food for their tables. But in these mountain communities, the instruction to plant large crops and to raise more food animals was taken up and food self-sufficiency is much stronger. In the planting and harvesting, recently the bean crops, the working groups travel by foot or horseback, to spend several days assisting each other in useful work. This tradition of multi-family work parties, originally known as “guateque,” (which refers to the accompanying feast and party) was diminishing but is now growing again. Larger, more productive fields are now possible within an indigeneity tradition of reciprocity. At the Fray Benito community, the current project is in rebuilding a casaba-producing complex that has been in the family for generations. This ancient Taino food, product of the yuca or manioc, is presently more in demand. Groups of women in Cajobabo and Tames are starting home-based enterprises, in fashioning textiles and clothing, and in setting up home-based small animal husbandry for home consumption and commerce. As the COVID-19 pandemic comes under control and public transportation becomes more available, the tourism industry is again growing. Plans are underway in the Gran Familia for a large gathering to dialogue with educators. National stories are breaking in Cuban media about the surprisingly high rates of Indigenous DNA in the Cuban population. The highest rates of Cuban Indigenous DNA are reported among Cacique Panchito’s folks. — Jose Barreiro Tsundzukani Daycare Centre Kitchen Upgrade Project South Africa Technical report, 30th January 20223/2/2022 The Kitchen Upgrade project began in December 2021 at the Tsundzukani Bright Eye's Daycare Center, during the great rains of this season. With much joy and enthusiasm, our team met at Cashbuild, the local materials supplier in the Acornoek community. We selected and ordered the main building materials and equipment needed for our work, which were delivered the same day. The firm's manager thanked Plenty Canada for the ongoing support the organization has provided to the Tsundzukani Daycare for several years.

The original Center's kitchen facilities were very rudimentary as one can see from the images accompanying this report. Therefore, our project was based on an upgrade of the entire building structure into a more adequate standard to provide a healthy and safe environment for large scale meal preparation. The first construction step of the kitchen upgrade was to increase the size of the building structure. The next step was to install the roof trusses and continue with the exterior wall plastering, but the next big rain falls interrupted our work for a week or so. We were all happy for the rain anyway so it was a blessing in disguise. Our work continued in the next couple of days with the sun shining and the builders being able to complete the plastering of the exterior walls and install the new galvanized roof sheets just in time before the next downpour took place. Now that the roof was up the builders were able to plaster the interior walls and begin to install the wooden structure to support the ceiling which was successfully completed. The cornices were also placed and the first coat of paint was applied. The large window was additionally installed so to bring more light and fresh air into the kitchen environment, with a view to the Center's vegetable garden. As per our project plan, it is proposed to install an extra rain catchment and storage system in order to provide a separate running water supply to the kitchen facilities. This improvement will make the meal preparations and clean up easier and more sanitary, as currently there is no direct running water line into the building. Our building work is almost complete and if the weather permits it will take a couple of weeks to finish it up. The construction of two concrete tables around the interior walls will be added to the kitchen sink table. The kitchen floor will be painted with stoep paint to make it easier to sweep and mop. A second coat of paint will also be applied to the interior walls and ceiling. Other minor finishing jobs will be also accomplished. — Mwana Bermudes Plenty Canada is currently developing an innovative water and waste management system at its head office location in Lanark, Ontario. We are seeking to incorporate and integrate methods and technologies into the renovation of our “Makwa Inn” multipurpose space that will reduce consumption of potable water, reuse both water and nutrients, as well as release the used water in both a sanitary and ecologically sound way. We are viewing both water and nutrients as part of a cycle that should be cared for and designed to be resilient.

There is currently a crises of waterway pollution in both urban and rural environments. Centralized municipal wastewater treatment plants collect human wastes and provide cursory treatment before sending millions of litres of water into natural waterways. This water is high in nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as biological material, all of which starve water of oxygen. This process is called “nutrification,” and leads to a variety of destructive problems such as algae blooms and habitat loss for marine life. The contaminated water comes from us, from our bodies and from our farmlands through the foods that we are eating. In a way, we are stripping our soils of nutrients and dumping them directly into waterways through our sewers. Farmland Is often fertilized through artificial fertilizers or raw manure. These fertilizers filter into the soil and much of the nutrients are lost to groundwater before plants can make use of them. This contaminated ground water can filter through aquifers and drinking water supplies and eventually natural water ways, leading to the same issues of “nutrification” previously mentioned. Another concern in heavily populated rural areas, such as around lakes, is septic fields. Current basic standards of wastewater treatment do not necessitate a high level of nutrient removal, and the nutrients from our homes can end up in our lakes, turning once clear water into murky green ponds. A solution to many of these problems is composting. It is a process that is often misunderstood, and when it comes to composting human wastes, often vilified. By collecting and using simple natural processes to compost our waste we can convert these nutrients into sanitary and chemically stable fertilizers that do not leach nutrients in the same way commercial fertilizers or raw manures do. The implementation of this process closes the nutrient loop and returns the nutrients we have taken from the land back to the land. True composting is a natural process powered by “thermophilic” bacteria, bacteria that live in an oxygen rich environment and thrive off of, and release, heat. These bacteria are ubiquitous in all natural environments and given the right circumstances will eat and digest our bodies unused nutrients while also starving out and cooking harmful bacteria such as E. Coli and various other pathogens and parasites which may be present in our leavings. The trick is getting the carbon – nitrogen balance correct. Properly maintained compost piles can reach temperatures of 70 degrees Celsius, temperatures which can kill most pathogenic bacteria and parasites within minutes. A pile can remain at these high temperatures for weeks or months at a time. Plenty Canada will be incorporating a series of accessible indoor and outdoor composting toilets with a composting shed to the property to be used to collect and compost our bodies nutrients and return them to the land. — Garrett Johnson |

|

-

Home

- Donate

-

Projects

-

Canada

>

- Plenty Canada CampUs

- The Healing Places

- Two-Eyed Seeing Bird Knowledge

- Niagara Escarpment Biosphere Network

- Greenbelt Indigenous Botanical Survey

- Great Niagara Escarpment Indigenous Cultural Map

- Ginawaydaganuc Indigenous Food Sovereignty

- Indigenous Languages and Cultures Programs >

- Wild Rice

- Good Mind Grappling (partnership)

- Ginawaydaganuc Village (partnership)

- Youth Programming >

- Americas >

- Africa >

-

Canada

>

- News

- Resources

- Partners

- Contact Us

Our Location266 Plenty Lane Lanark, Ontario Canada K0G 1K0 (613) 278-2215 |

Donate to

|

Subscribe to our Newsletter |